Report on Case Study of Kowloon Bay Health Centre

Chapter 1

Background and Objectives

1.1 Background

1 . In May 1999 the Kowloon Bay Health Centre ("KBHC"), in the Kowloon Bay area of Kwun Tong District, commenced operation. The KBHC consists of a government health care centre and a subvented nursing home. Services provided include :

(a) a general out-patient clinic, (b) a student health centre, (c) an integrated treatment centre for sexually transmitted diseases, skin diseases and AIDS and HIV patients ("the Integrated Treatment Centre"), (d) an X-ray unit, and (e) a nursing home facility called the Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Nursing Home ("the Home").

2 . The planning of the KBHC started in 1983. The KBHC was intended to be a general out-patient clinic which was to be developed in conjunction with a neighbourhood community centre. Its scope was expanded in 1993 to include the present range of services. When news about the revised scope of the KBHC, particularly the inclusion of the Integrated Treatment Centre, became known to the local community in 1995, there were objections leading up to violent protests to its establishment.

3 . Some of the residents of Richland Gardens ("RG"), a Private Sector Participation Scheme development, located next to the KBHC, demanded that the KBHC be re-sited. Following representations made by the District Board of Kwun Tong, the Government agreed to shift the site 25 metres further away from RG. However, the request to re-site at a different location was rejected by the Government.

4 . A concern group lodged a complaint with the Ombudsman's Office claiming insufficient consultation by the then Health and Welfare Branch. The claim was supported by the findings of the Ombudsman in October 1996.

5 . Since the Government turned down the request for the re-siting of the Centre in December 1995, some of the residents launched a series of protests, including demonstrations on their home ground, outside the Government Secretariat on Lower Albert Road and the Legislative Council Building, and a petition to the Chief Executive of the HKSAR.

6 . These residents also put up a large number of protest banners around the KBHC site and erected an illegal wooden shed just outside the RG boundaries, which was used by these residents as a convenient gathering place and it came to be called the "Command Post". When construction work for the KBHC started in October 1996, these residents also attempted to block the construction site, resulting in police arrests.

7 . In May 1999, the KBHC commenced operation. This was the point when a small but vocal group of residents (the "Minority Group") came into direct contact with staff and users of the KBHC who then became the target of the Minority Group. The KBHC staff and users were subject to verbal insults, physically stopped, interrogated on RG premises and followed as they walked by or through the RG premises to the bus stops, taxi stand and other ancillary facilities.

8 . The Equal Opportunities Commission ("EOC") observed that the protests were initially directed against the Government for inadequate consultation, followed by active blocking of the construction site in the second phase, and harassment of the KBHC staff and users in the third phase. The targets and the subject matter of the protests shifted from time to time .

9 . In June 1999, the Hong Kong Coalition of AIDS Service Organisations complained to the Legislative Council ("LegCo") Complaints Division regarding the handling of the KBHC case by the Government. In response, LegCo members decided to convene a case conference with the relevant Government departments, the EOC and other concerned parties.

1 0 . The EOC became actively involved with the KBHC case in the third phase of the protests by the Minority Group which commenced with the opening of the KBHC in May 1999. As the acts complained of became more severe and targeted the KBHC staff and users, the EOC took the following actions:

(a) the EOC set up a temporary office at the KBHC from 21 June to 17 July 1999 to assist aggrieved persons; (b) the EOC contacted various service organisations and explained to them the protection provided under the Disability Discrimination Ordinance ("DDO"); (c) the EOC issued about 10,000 letters to residents in RG and the neighbouring estates reiterating the concern the EOC had in respect of discriminatory activities and explaining the provisions of the DDO; (d) the EOC arranged a number of public education programmes from May to July 1999 in the neighbourhood, comprising exhibitions, talks and shows and also placed pamphlets and posters in the Centre advising people of their rights to complain to the EOC.

1 1 . The actions of the EOC resulted in the acts being complained of subsiding in July and August of 1999. However, in early September, these acts complained of were revived and became even more serious than before.

1 2 . Since the Centre opened, it was made clear to its users and the staff that complaints against discrimination could be lodged with the EOC. However, it was the view held by some of the victims, that a complaint against the Minority Group would be too confrontational and hostile, making it difficult to heal a badly wounded community relationship. Additionally, for the victims to lodge complaints, they must disclose their identities, thus making them vulnerable to disclosure of their disabilities and further attacks. This was particularly difficult for AIDS and HIV patients.

1 3 . To further encourage complaints to be lodged with the EOC, the EOC invited representative complaints from employers of the staff at the KBHC and by relevant service providers on behalf of aggrieved persons.

1 4 . Recognising the difficulties the victims would have with actual complaints, the EOC began its own inquiry in early September. This was an unusual step to take as without formal complaints of discriminatory acts, the EOC had to rely on its staff to collect evidence. In mid-September 1999, the EOC announced its decision to conduct a case study into the KBHC case. In addition to surveillance, sporadic checks and conducting a survey, the EOC staff interviewed KBHC staff and users extensively over a period of about four weeks.

1 5 . The operation of the KBHC and its management, staff and users, as well as many of the non-hostile residents of RG, were all adversely affected as a consequence of the activities of the Minority Group. The KBHC suffered from high staff loss and difficulty in recruitment, inability to extend operating hours and to attain full capacity. KBHC staff leaving after the evening shift at 10 p.m. needed to be fetched by family members, taken to other public transport connections in taxis arranged for by the KBHC management, or take a circuitous route to the bus stops, being a dimly lit mud path which was unsafe for the staff members (who mainly comprise women). The majority of RG residents who had remained silent suffered through the shame made obvious through public opinion and the media. In fact, local real estate agents attributed an apparent drop in property prices in September 1999 to the public condemnation of the discriminatory acts. The public, according to media reports, was particularly incensed when the staff taking care of the aged were attacked.

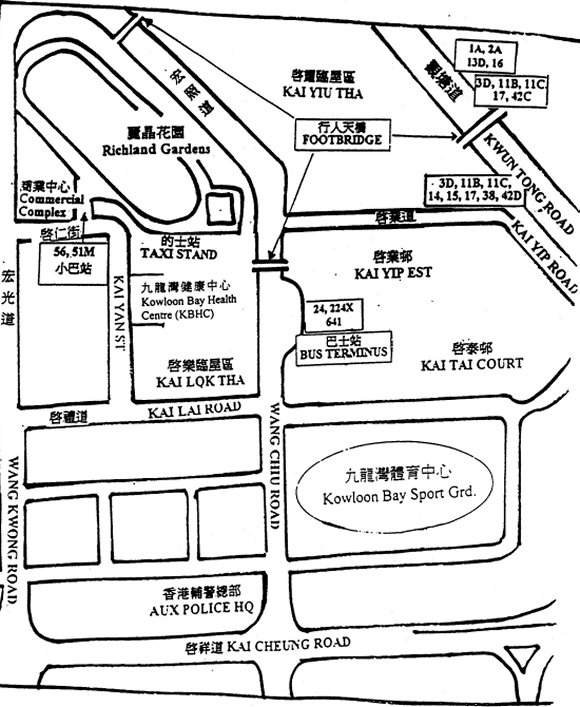

1 6 . A Location Map of KBHC and a chronology of events are at Appendices 1 & 2 respectively.

1.2 Study Objectives

1 . The purpose of conducting this case study is to -

(a) allow victims to put their grievances on record with the EOC without disclosure of their identities and without having to face the respondents under the complaint mechanism of the DDO; (b) enable the EOC to identify more specifically acts of discrimination and vilification, the causes of such acts and the ways to handle such incidents in future; and (c) enable the EOC to make recommendations regarding areas of concerns, including the planning of similar facilities in future.

1.3 Methodology

1 . For the preparation of this report on the case study, the EOC reviewed all related correspondence and documents on hand, including media reports, comments from Government departments, concern groups and other interested parties including the RG Owners’ Committee, the property management company for RG (Shui On Properties Management Limited), the Kwun Tong District Board and the Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Nursing Home .

2 . A number of Government departments was contacted by the EOC regarding the planning, establishment and operation of the KBHC and the consultation and liaison with those affected by the KBHC. These departments included the Department of Health, the Urban Services Department, the Lands Department, the Buildings Department, the Planning Department, and the District Office (Kwun Tong) of the Home Affairs Department. The EOC also sought the views of the Health and Welfare Bureau regarding the question of right of access via RG premises by general members of the public and KBHC staff and users.

3 . After the EOC announced its intention to conduct this study in mid-September 1999, it received only eight letters from members of the public mostly written by RG residents. The main thrust of these letters was that a new road should be built for use by the KBHC staff and users.

4 . The EOC interviewed in September 1999 a total of 157 KBHC staff and users to obtain first-hand accounts of the acts complained of.

5 . As a result of these efforts, formal complaints relating to these acts were received. As at the release of this report, a total of 10 complaints have been received by the EOC.

6 . The EOC has formally commenced its complaints handling procedure in relation to these complaints. While the EOC cannot disclose the details of the complaints, it will publish periodic progress reports.

Chapter 2

Survey and Interviews

1 . As most KBHC staff and users who have been affected by the discriminatory acts were initially reluctant to lodge complaints with the EOC, the EOC decided to approach the KBHC staff and users and record their experience on the basis that they would not be identified in the EOC report. The EOC also conducted a survey of the KBHC staff and users.

2 . From 21 to 27 September 1999, a team of six EOC staff visited the Centre daily and approached the 150 odd staff and 80 residents of the Home. The EOC also spoke to about 250 Centre patients and visitors during this period.

3 . These contacts provided information sufficiently indicative for the EOC to gauge the extent of discrimination experienced by the KBHC staff, users and visitors.

4 . Of the 150 staff members of the KBHC approached, 78 (or 52%) agreed to be interviewed. Of those interviewed, 49 (or 63%) reported they experienced some form of discriminatory treatment. In respect of the users and visitors of the KBHC, 79 were successfully interviewed, of whom only 5 (6%) reported discriminatory treatment. The EOC believes that the low percentage recorded is not indicative of the extent or frequency of discriminatory acts but because of the visitors'lower attendance rate compared to that of KBHC staff members, and the fact that the KBHC visitors were not easily recognised by the Minority Group.

5 . Of the female staff interviewed (totalling 63), 71% reported having been harassed whereas only 27% of the male staff interviewed reported the same experience. The majority (75%) reported that the harassment took place near the Command Post.

6 . As regards actions that should have been taken, 59% thought that the Government should have done more, for example, by demolishing the Command Post, stepping up police patrols, etc. A total of 29% of the respondents mentioned transport needs as a priority for action whereas 12% thought that more public education was required.

7 . A detailed breakdown of the survey results is at Appendix 3.

Chapter 3

Key Issues and Observations

1 . As a result of the documents review and the survey findings, the EOC has identified five key issues that have attracted considerable public debate. These key issues are:-

(a) the display of vilifying banners and the threat posed by the Command Post;

(b) the discriminatory acts of the Minority Group, the reluctance of the victims to lodge complaints with the EOC and the difficulties encountered by the EOC in collating evidence and identifying respondents;

(c) the right of the KBHC staff and users to pass through RG premises;

(d) the lack of public transport means close to the KBHC; and

(e) the lack of effective planning of the KBHC, appropriate consultation with those affected and co-ordinated effort in reducing friction.

Chapter 4

Vilifying Banners and the Command Post

4 . 1 Banners

1 . For several years before the Centre opened in May 1999, banners and placards had been put up on Government land adjacent to RG. These banners and placards carried slogans criticising the Government for not consulting the local residents on the project and the Government's decision not to re-site the KBHC to some other location.

2 . Nearer the time when the Centre opened, banners and placards directly attacking AIDS services were also found along Kai Yan Street (where the KBHC is situated) and all over the front of the KBHC building. Slogans such as "AIDS keep away", "The elderly and children are vulnerable; AIDS and venereal diseases should stay far away" were used.

3 . In April 1999 when construction of the KBHC building was almost completed and signage had to be put up by the Architectural Services Department, those banners and placards placed on the KBHC building were removed by the Government. As soon as the building was completed and handed over to the Department of Health, banners and placards reappeared.

4 . When the EOC wrote to the Urban Services Department ("USD") asking for the removal of unauthorized banners on Government land surrounding the Centre, the USD wrote back with a host of questions, such as whether the residents had applied for permission to put up these banners and whether any other Government departments were taking parallel enforcement actions. The USD also made the point that it could not take action without the coordination and leadership of the District Office.

5 . When asked why it had not taken the banners down, one Government department involved sided with those who had put up the banners and claimed they were entitled to their freedom of expression.

6 . In late May 1999, the EOC staff visited the KBHC and heard the staff's grievances about the banners and placards as well as the discriminatory acts they experienced. A joint operation by the USD, the Police and the Lands Department, led by the District Office, was ultimately carried out to remove the banners on 23 June 1999, just a few days before the Integrated Treatment Centre began operation.

7 . The operation was not entirely successful. While all the banners in front of the KBHC were removed, two banners carrying vilifying slogans were left untouched because of residents' confrontation on site. They were removed by the Government in September 1999 after a storm in August had washed away most of the words on the banners. They had read "AIDS, venereal disease and skin disease will affect the elderly and the children".

4 . 2 The 'Command Post'

1 . Apart from the banners there was also the Command Post. This was a wooden shed erected illegally in about April 1996 at the corner of Kai Yan Street next to an entrance to RG. The Minority Group often gathered at the shed, where its members could easily see and identify people going in and out of the KBHC. When staff and users passed by, or intended to enter RG, they would be harassed or denied access by these members gathering at the Command Post.

2 . From the beginning, the Lands Department was aware that the Command Post was an illegal structure on Government land. The Department said that it had had six meetings with the District Office (Kwun Tung) ("DO(KT)"), commencing in 1996, but no action was taken by DO(KT).

3 . In September 1999 public opinion began to mount, questioning why the Government should tolerate the illegal structure. According to the Lands Department, it took up the matter again with DO(KT) and urged it to coordinate the removal exercise.

4 . On 28 September 1999, more than 1300 days (as counted by the RG residents themselves) since the illegal structure was put up, the Command Post was removed in a joint action by Government departments.

4 . 3 Banner Challenges

1 . The contents of the early banners essentially related to Government planning and lack of consultation.

2 . When the KBHC opened in May 1999, new banners were put up and the slogans changed from being anti-government to vilification of persons with AIDS or HIV.

3 . In the context of the DDO, these banners and placards presented a particular set of problems. The main problem was that the EOC itself did not have the power to remove them or direct others to do so, contrary to misconceived notions by some members of the public. Furthermore, the EOC could not activate its complaint handling mechanism or its formal investigation power as there was no named respondent. Even if a complainant were available, there was no way that the EOC could identify the person(s) responsible for putting up the banners.

4 . The EOC takes the view that the slogans on these banners were so patently discriminatory and vilifying that it should have been able to seek a court action directing the Government departments to remove them.

5 . The delay in removing the banners and placards resulted in four complaints finally being lodged against various Government departments.

Chapter 5

Confrontations

5 . 1 The Situation

1 . Since the Centre opened, the following incidents have been reported -

(a) The Minority Group crowded outside the entrance of the KBHC and jeered; members also shouted from the Command Post at passers-by coming out of the KBHC. (b) The Minority Group jetted water onto the pavement after visitors came out of the KBHC. (c) On two occasions, the Minority Group barged into the Home. In the first incident, on 27 May 1999, the Minority Group, led by the Chairman of the RG Owners' Committee, forced its way into the Home to "inspect its hygienic condition". In the second incident, on 2 September 1999, the same people demanded to sit in on a meeting of the Community Liaison Group, using foul language and refusing to leave. The Police were called in.

2 . In addition to the incidents reported above, there were other incidents which were of concern. One in particular involved EOC staff members.

3 . On the evening of 6 September 1999, a female EOC staff member covertly accompanied a group of 11 female staff members from the Home when they went off duty at 10 p.m.. A male EOC staff member was also present but had left ahead of the others to observe the situation. Shortly after 10 p.m., the group of women walked towards the Command Post. As they approached, the Minority Group at the Command Post immediately stood up and tried to stop them from going through the entrance to RG. Then the Minority Group gathered around the women shouting and yelling at them in abusive language. When the women continued walking, they were stopped and cornered near the taxi stand inside RG, some 20 yards from the Command Post. At that time, about four security guards came over from various directions. They asked the women for the purpose of their visit. This was followed by an incident involving a reporter and a photographer. Then the women went back to the entrance and dispersed on their own. The Police arrived later. The reporter, the photographer and the EOC staff members were driven to the Ngau Tau Kok Police Station at about 10:45 pm.

4 . The incident on 6 September involving the EOC staff members highlighted another problem that was faced by the EOC - the lack of identification of possible respondents. This was only resolved with the assistance of the Police who were later able to provide the names of some of those involved.

Chapter 6

The Right of Access

6 . 1 Implied Invitation

1 . As can be seen from the Location Map, the KBHC was established on one side of RG and most of the public transport access on the other side of RG. The most direct way for KBHC staff and users to get to these is through RG. The transport planning, or lack thereof, lent itelf to friction between the Minority Group and the KBHC staff and users. Government legal opinion on the issue has not been helpful and adds to the uncertainty created by the layout of the estate.

2 . Although RG is a private residential estate, it contains within its boundaries a number of facilities which may be used by non-residents. These include shops, restaurants, mini-bus facilities and a taxi stand. Certainly the shop keepers and the restaurant owners would have a vested interest in ensuring that members of the public visit their facilities. The presence of some or all of these facilities within the estate, and the reference in the Deed of Mutual Covenant ("DMC") to common areas of the estate being for the benefit of persons including "invitees", suggests that the public may enter and use the facilities at RG by invitation. In other words, there is an implied invitation that any member of the public may enter the estate to visit the shops, a restaurant, or the like.

3 . As this is an implied invitation, legally it may be withdrawn at any time. However, if such withdrawal or modification of the implied invitation affected only, or predominantly, persons connected with the KBHC, this would amount to unlawful discrimination under the DDO.

4 . The DDO states that it is unlawful to discriminate against a person with a disability or a person who is an associate of a person with a disability by refusing to allow him/her access to premises that the public or a section of the public is entitled to enter or use.

5 . Is the public or a section of the public entitled to enter or use the facilities of RG? The answer is yes, both in terms of land law and in terms of anti-discrimination law.

6 . In the course of this case study, the EOC has not been able to find any withdrawal or modification of the implied invitation to members of the public to enter and use the facilities at RG. As far as the EOC is aware, there has been no decision by the Owners’ Committee, nor any resolution of the owners, in respect of withdrawing or modifying the invitation to the public to enter the premises to use the facilities. It appears that the incidents which have given rise to persons connected with the KBHC being refused access to the facilities at RG have been initiated by a small minority of residents acting without the mandate of all the other residents or owners. This not only gives rise to possible breaches of the implied terms of the DMC by such a minority group of residents, it leaves them individually liable for unlawful acts of discrimination.

6 . 2 Layout of the Estate

1 . Some of the incidents which have given rise to refusal of access have also involved the question of whether the public is entitled to enter or use RG solely for the purpose of walking through the estate to take a short cut. This issue is separate and distinct from that of entry for use of facilities, and the answer is less clear.

2 . There is a path which cuts across the estate between Kai Yan Street and Wang Chiu Road. It is relatively short in length, perhaps no more than 60 metres, and it provides easy access for persons wishing to get from one street to the other without taking a longer circuitous route. It cuts through the estate in almost a straight line and appears to be a continuation of the carriageway of Kai Yip Road. Members of the public have been using it freely as a thoroughfare since RG was established some 14 years ago.

3 . The EOC considers that there are conflicting indicators as to whether there is a public right of way in respect of this thoroughfare. The physical layout of the path suggests that there is such a right of way; not only does the path appear to run in a straight line as a continuous part of one carriageway, the taxi stand is situated along this path, as is a group of small shops which seem to be part of a larger market. There are also signs within the estate, which look like government street signs, which point to a footbridge over Wang Chiu Road by way of steps up to and along a podium. Even if this access to the footbridge via the podium were intended only for the residents of RG, and even if the podium were only for the use of residents, it nevertheless sends out a conflicting message that members of the public may enter RG in order to cross Wang Chiu Road.

4 . On the other hand, there are metal barriers at each end of the thoroughfare with signs prohibiting unauthorised entry. These suggest that, although the public may have accepted the path as a public right of way, and have been using it as such, the owners have not dedicated it as such and therefore it does not form a public right of way.

5 . Although the EOC cannot categorically state whether members of the public have the right to enter RG for the purpose of simply cutting across the estate without visiting the shops, etc., under the DDO, it is nevertheless unlawful if only, or predominantly, persons connected with the KBHC are stopped from using this path as a shortcut.

6 . 3 Public Transport Means

1 . The various public transport means are marked on the Location Map. It must be noted that none of these was planned to facilitate access to the KBHC for staff and users.

2 . On the request of the KBHC staff and users, the EOC has liaised with the Transport Department and the Kowloon Motor Bus Co. ("KMB") to provide additional bus stops closer to the KBHC.

3 . The EOC contacted KMB directly in October 1999. KMB has agreed in principle to re-route three of its bus services subject to the usual approval and consultation required. The EOC was most encouraged by the accommodation provided by KMB.

4 . The Transport Department has already arranged with the minibus operators to provide an additional stop right outside the KBHC. This arrangement commenced on 7 November 1999.

6 . 4 Planning

1 . According to the Hong Kong Government's Planning Standards and Guidelines, general clinics should be centrally located within the districts they are intended to serve. They should be easily accessible by public transport and, where possible, be sited close to other community facilities to which residents require daily access.

2 . In planning terms, the Government policy must be in favour of integration of facilities with the local community rather than segregation. This would also allow effective utilisation of all facilities and the transport network for the area.

3 . In respect of the KBHC, the EOC has found that 40% of the patients using its out-patient clinic are residents of RG. This shows a need for community integration and non-discriminatory behaviour.

4 . It is essential that the planning of a residential estate which provides infrastructure linkages to the surrounding area, clearly addresses the question of access by non-residents. In the case of the KBHC, the lack of legal and planning certainty regarding public access through RG became a source of friction.

6 . 5 Consultation and Co-ordination

1 . In the KBHC case, the consultation with the local community on the expansion of the scope of services of the KBHC from a general clinic to a multi-purpose health care centre took the form of an information paper, presented in March 1995 at the Social Services Committee of the Kwun Tong District Board, without any reference to its exact location.

2 . Public consultation and support is a critical factor for the success of such facilities. A lack of full disclosure by the Government would only increase the community's distrust of the Government and apprehension of the services for the disabled.

3 . The DO(KT) should have a pivotal role to play in co-ordinating district affairs and garnering support from the local community.

4 . The District Management Committee under the District Officer's chairmanship should be a proper forum to consider and agree upon what actions to take in respect of controversial issues. The EOC has inspected the minutes of the District Management Committee meetings for the period February 1992 to September 1999 and has found progress reports on the KBHC in the early days of inception, and the opening schedule, but no indication of efforts to tackle the problems.

5 . The EOC has also found that the DO(KT) has been unable to draw out the views of the majority of the RG residents who, although silent, might not have any great sympathy for the actions of the Minority Group.

6 . The EOC had publicly urged that the Owners' Committee make clear its position. The Owners' Committee issued a statement on 26 September 1999 attempting to distance itself from the actions of the Minority Group.

7 . The lack of co-ordination by the DO(KT) is also reflected in the way it handled the removal of banners by the USD and the dismantling of the Command Post requested by the Lands Office. The DO(KT) was expected to take the lead and co-ordinate the effort. It would seem that, despite requests from other Government departments, nothing much happened until very late in the day.

Chapter 7

EOC Powers

1 . The existing powers of the EOC provide that the EOC may take the following remedial actions:

(a) Formal investigation (b) Civil action assisted by the EOC (c) Civil action in the EOC's name

Formal investigations may be conducted by the EOC if it thinks fit, and must be conducted if requested by the Chief Secretary for Administration. The main requirement is that the EOC must set out terms of reference for the formal investigation and the EOC must confine itself to the matters set out therein.

2 . Generally speaking, there are two types of formal investigation that the EOC has the power to conduct: a "belief" investigation where an unlawful act is believed to have been committed by a named respondent, or a "general" investigation where there is no person named in the terms of reference. The latter type of formal investigation usually concentrates on an area of activity, such as systemic discrimination in a particular field. Unless the EOC conducts a belief investigation, it cannot compel persons to provide information, nor can it issue enforcement notices.

3 . Even where the EOC is able to identify a named respondent in order to conduct a belief investigation, such respondent must be given the opportunity to make representations to the EOC before the commencement of a formal investigation and also has the right to seek judicial review of the EOC's decision to conduct the investigation. Furthermore, any enforcement notice issued by the EOC thereafter can only be enforced by application to the court. This is not an automatic procedure and the court may reconsider all the matters giving rise to the issue of the enforcement notice.

4 . The EOC also has a discretion to give assistance to applicants who wish to institute civil proceedings in court. However, this power is limited to proceedings by aggrieved persons against named respondents. It requires an identifiable respondent and a complainant who is prepared to come forward and be the plaintiff in a tort action.

5 . The EOC has found in the course of this case study that the fear of public identification on the part of victims of discrimination seriously inhibited aggrieved persons from lodging complaints with the EOC. In particular persons with stigmatised disabilities are vulnerable when it comes to public disclosure of their disabilities. A person with HIV or AIDS will be extremely apprehensive about taking legal action which will involve him/her having to be identified as a person with a particular disability. He/she will also be reluctant to be named in the media. This is an issue which needs to be addressed in its own right, and the EOC will be making separate representation to the courts that the names of persons with HIV or AIDS should not be disclosed in court actions or reported in the media.

6 . As for legal action by the EOC in its own name, again this can only be in respect of an unlawful act committed against an aggrieved person by a named respondent. The aggrieved person would need to give his/her consent to the action and would need to testify in court as to the actions committed against him/her by the respondent. Similarly, the EOC can only ask the court for a declaration that a particular act is unlawful if a tort action has been brought against a named respondent. As for the power of the EOC to seek an injunction, this applies only to limited situations, none of which is applicable in the context of the KBHC case.

7 . In fact, in the context of the KBHC case, the EOC has not had to deal with just the problem of the reluctance of complainants to come forward or the difficulty in identifying respondents. The problem was compounded by the legal uncertainty that surrounded the issue of access. If the EOC had been able to apply directly to the court for a declaration in respect of the issue of access, without the necessity of instituting a tort action, there would have been a swift resolution of the matter and certainty for all parties.

8 . Similarly, if the EOC had been able to apply directly to the court for an order directing the removal of the vilifying banners, this would have provided the impetus and the legal certainty for the relevant Government departments to take prompt action to remove the banners.

9 . In the EOC's view, where there are issues of such public importance which affect the community at large, swift action and legal certainty are imperative.

1 0 . The EOC has therefore proposed that the Government amend relevant legislation to enable the EOC to take remedial action in its own name where appropriate. Specifically, it seeks the power to seek declaratory and/or injunctive relief in its own name, in respect of all unlawful acts and unlawful conduct under the anti-discrimination laws, as well as in respect of discriminatory policies and practices. Several of the incidents described in this case study illustrate the problems associated with the EOC's existing powers, and highlight the need for some amendment to the legislation. It is not the EOC's intention to become a prosecution agency. Hence, this recommendation is limited to issues of public interest.

Chapter 8

Summary of Recommendations

In the course of conducting this study, the EOC acknowledges that more could have been done to mobilise RG residents to support the operation of the KBHC and its staff and users. This has been a lesson for the EOC and for all Government departments involved. Accordingly the EOC recommends the following:

1 . That the Health and Welfare Bureau should work closely with the Planning Department and the Department of Health on a clear set of guidelines setting out the location of sensitive services and the support facilities and infrastructure requirements;

2 . That community integration should be adopted by Government as the planning policy in respect of the establishment of this type of centre and that maximum utilisation should be made of the community facilities and infrastructure in the neighbourhood;

3 . That once decisions have been made on the siting, there is a need for the Department of Health, the various agency support groups (including the EOC) and the local District Office to come together and adopt a strategy for consultation and to garner support from the local community. The District Office concerned should take up a key coordinating role in the consultation and liaison process;

4 . That in providing planning approval for this type of centre, the Government should consider the transport needs of staff, users and visitors to the centre and provide clear access to and from the centre;

5 . That having regard to the difficulties experienced in this situation, the EOC should be given the power to seek declaratory and/or injunctive relief in its own name, in respect of unlawful acts and unlawful conduct under the anti-discrimination laws, as well as in respect of discriminatory policies and practices; and

6 . That having noted that persons with disabilities are vulnerable when it comes to public disclosure of their disabilities, the courts should exercise their discretion and order that the names of such persons, particularly HIV or AIDS patients, should not be disclosed in court actions or reported in the media.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

THE KOWLOON BAY HEALTH CENTRE INCIDENT

Chronology of Events

| Year | Month | Events |

| 1983 | KBHC project started out as a general out-patient clinic to be developed in conjunction with a neighbourhood community Centre. | |

| 1985 | Sale of Richland Gardens (RG) flats. | |

| 1993 | Scope of Centre was expanded to include an Integrated Treatment Centre (ITC) for skin diseases and HIV infection, a Radio-diagnostic & Imaging Centre (RIC), Student Health Service Centre (SHC) and a Nursing Home (NH). | |

| 1995 | March | An information paper on the project was presented to the Social Service Committee of the Kwun Tong District Board (KTDB). |

| July | The project was upgraded to Category A in the Public Works Programme. | |

| July | Protests by RG residents. Kwun Tong District Office had since begun a dialogue with RG residents on a need basis. | |

| October | KTDB requested to relocate the KBHC to another site in the Kowloon Bay area. | |

| Decemeber | Government announced its decision to shift the KBHC 25 meters southwards, slightly away from RG. | |

| Decemeber | The Lands Department (LD) was made aware of banners mounted on government land. It had since held many meetings with District Office (Kwun Tong). | |

| 1996 | January | An illegal structure was found along Kai Yan Street near the entrance to RG. |

| February | KTDB urged the Government to relocate the KBHC for the third time. | |

| April | The site was handed over to the Architectural Services Department (ASD) on 29 April. The "Command Post" became the regular gathering point for protesting residents. | |

| August | The Richland Gardens Kowloon Clinic Concern Group (麗晶花園九龍灣診所關注組) was formed under RG Owners' Cimmittee. | |

| October | Construction work began, after a delay of six months. Residents obstructed works being carried out on site. Residents protested against the Police for excessive use of force. Demonstration rally took place on 14 October outside the Home Affair Department (HAD), ASD, Police Headquarters and the Government Secretariat. | |

| October | The Ombudsman Office investigated a complaint about inadequate consultation lodged by a group of RG residents. It concluded that "the public consultation purportedly to have been conducted in this case cannot satisfy the yardstick for fair, adequate, meaningful and timely consultation which any open and responsible government should adopt. In the circumstances, this office considers that the residents of the estate had not been adequately consulted on this project and hence concludes that this complaint is substantiated." | |

| 1998 | January | Demonstration outside the Legislative Council Building. |

| March | Representatives from the ASD, the Environmental Protection Department (EPD), the Police, the Urban Services Department (USD) and the Department of Health (DH) started regular meetings with RG residents to discuss issues. | |

| November | Petition to the Chief Executive, HKSAR. | |

| 1999 | April | Residents obstructed ASD staff from putting up signage on KBHC. |

| Banners were removed by the Government, but reappeared soon after the handing-over of the building to DH. | ||

| May | DH formed a Community Liaison Group (CLG) to address residents' concerns and to promote public education. | |

| The NH commenced operation on 5 May, and the outpatient clinic on 26 May. | ||

| Harassment of Centre staff and users by a small group of RG residents began. | ||

| Centre staff were turned away from using RG passage. | ||

| The small group of RG residents complained against KBHC on aspects such as refuse disposal, high noise and emission level of the cooling system, radiation etc. | ||

| They urged the Government to provide special access and transport for KBHC staff and users. | ||

| June | SHC, ITC and RIC commenced operation on 14 June, 25 June and 29 June respectively. | |

| EOC set up a temporary office in KBHC from 21 June to 17 July in an effort to reach out. | ||

| Joint Government operation to clear vilifying banners on 23 June. | ||

| July | EOC received complaints against vilifying banners. | |

| The first LegCo case conference on KBHC held on 13 July. | ||

| September | A series of events took place between 2 and 13 September, including a demand to sit in a CLG meeting, denial of access to staff, users and carers to use RG passage. | |

| EOC announced its intention to conduct a case study and began extensive field work. | ||

| Demolition of the "Command Post" and removal of remaining banners on 28 September in a joint Government operation. | ||

| October | The second LegCo case conference was held on 4 October. | |

| November | A green minibus stop was set up in front of KBHC on 7 November. KMB indicated that it had no objection to the diversion of three bus routes via Kai Yan Street subject to Transport Department (TD) agreement and consultation with KTDB. | |

| The third LegCo case conference was held on 15 November. |

Appendix 3

Findings of survey conducted at the KBHC

The survey was conducted from 21 to 27 September 1999. A total of 157 Center staff, users and their relatives / carers visiting the Centre agreed to be interviewed.

A. Harassment experience by sex and status of respondents

|

Respondents |

Sex |

Experiensing |

||||||||||

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

Yes |

No |

Total |

|||||||

|

N |

(%) |

N |

(%) |

N |

(%) |

N |

(%) |

N |

(%) |

N |

(%) |

|

|

Staff |

15 |

63 |

78 |

(50) |

49 |

(31) |

29 |

(18.5) |

78 |

(50) |

||

|

Users |

0 |

33 |

33 |

(21) |

2 |

(1.5) |

31 |

(19.5) |

33 |

(21) |

||

|

Carers |

26 |

20 |

46 |

(29) |

3 |

(2) |

43 |

(27.5) |

46 |

(29) |

||

|

41 |

(26) |

116 |

(74) |

157 |

(100) |

54 |

(34.5) |

103 |

(65.5) |

157 |

(100) |

|

Experience of Harassment by sex

|

Respondents |

Male |

Female |

||||||||||

|

Harassed |

Not Harassed |

Sub total |

Harassed |

Not Harassed |

Sub total |

|||||||

|

N |

(% of sub total) |

N |

(% of sub total) |

N |

(%) |

N |

(% of sub total) |

N |

(% of sub total) |

N |

(%) |

|

|

Staff |

4 |

(27) |

11 |

(73) |

15 |

(100) |

45 |

(71) |

18 |

(29) |

63 |

(100) |

|

User |

0 |

(0) |

0 |

(0) |

0 |

(0) |

2 |

(6) |

31 |

(94) |

33 |

(100) |

|

Carers |

1 |

(4) |

25 |

(96) |

26 |

(100) |

2 |

(10) |

18 |

(90) |

20 |

(100) |

|

5 |

(12) |

36 |

(88) |

41 |

(100) |

49 |

(42) |

67 |

(58) |

116 |

(100) |

|

B. Forms of harassment acts

A total of 54 respondents had experienced one or more forms of harassment.

| % | |

| Use of abusive language / harassing remarks | 70 |

| Stopped and questioned when passing through Richland Gardens | 30 |

| Being stared at when passing through the "Command Post" | 10 |

C. Where did the alleged harassment acts take place?

| %

|

|

| Near the "Command Post" | 75 |

| Along other parts of Kai Yan Street | 12 |

| Outside the Center | 9 |

| Near the minibus terminus | 6 |

D. Respondents' reactions to the harassing acts

| % | |

| Re-routing | 60 |

| Ignored the acts and continued with the journey | 35 |

| Reported to the Police | 5 |

E. Which organisation should be responsible for stopping the harassing acts

23 respondents who had experienced harassment made the following comment

| % | |

| The Government as a whole | 69.5 |

| The Police | 17.5 |

| The Equal Opportunities Commission | 8.5 |

| The Lands Department | 4.5 |

F. What actions should be taken in respect of the harassing acts

A total of 51 comments were collected on actions required.

| % | ||

| Government actions | ||

| Removal of illegal structure | 31 | |

| Tough and active Government actions required | 12 | |

| Police should step up patrol / take tougher measures against the harassers | 10 | |

| Government should listen more to local opinions | 2 | |

| Change the present site into a rest garden to reconcile the differences | 2 | |

| Clarification of the right of way inside Richland Gardens | 2 | 59 |

| Transport needs | ||

| Setting up a mini-bus stop in front of the Center | 13 | |

| Independent transport facilities to be provided to staff and users | 10 | |

| Re-routing bus routes to cater for the needs of staff and patients | 4 | |

| A separate road to be built | 2 | 29 |

| Public Education & Communication | ||

| Residents to be given a clearer understanding of AIDS / HIV | 8 | |

| Stepping up liaison with RG residents | 4 | 12 |

| 100 | ||